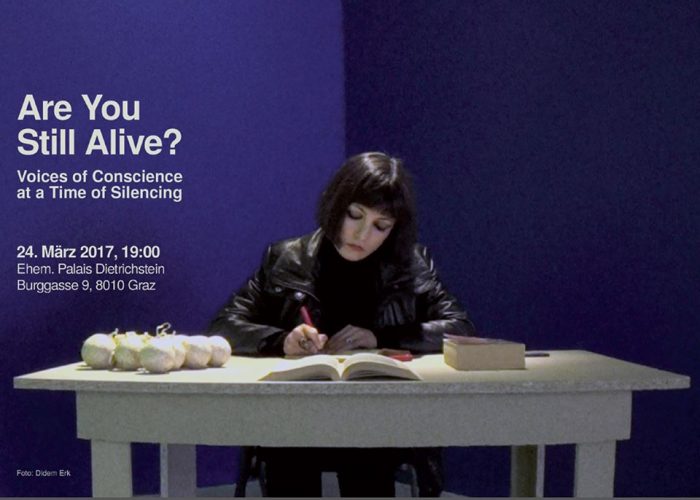

Are You Still Alive? – Voices of Conscience at a Time of Silencing

Are You Still Alive? – Voices of Conscience at a Time of Silencing

Venue: Steirische Kultur Initiative

Address: Burggasse 9, 8010 Graz

Opening: 24 March 2017, 7 pm

Dates: 25 March – 21 April

Artists:

Berat Isik | Didem Erk | Zeyno Pekünlü

Curators:

Isin Önol & Michael Petrowitsch

The exhibition, an intervention at a public office building in Graz, invites personal voices and artistic responses to the experience of witnessing the unspeakable at a time of silencing. In particular, it reflects individual, political, and artistic struggles within the current political landscape of Turkey.

Provoked by an ostensibly simple question, “What is going on in Turkey?”, the exhibition can be perceived as a geography-specific response, weaved from the subjective positions of the invited participants. While the country is going through a complex and historically intricate process, its inhabitants’ individual and collective acts today can only strive to contribute to possible futures, and conclusions about the historical facts. What they can show us today are individual efforts for staying safe, yet humane, dignified and gracious.

Berat Isik, Didem Erk, and Zeyno Pekünlü’s work, brought together in this particular context and exhibited at a non-conventional and atypical space for art, a public office for social security, juxtaposes individual positions that evoke hope, sympathy, and grace in the face of systemic atrocities that have replaced reasonable discourse. The title Are You Still Alive? is borrowed from a recent exhibition by Diyarbakir-based artist Berat Isik, which shaped the main framework for this exhibition.

Artists & Works:

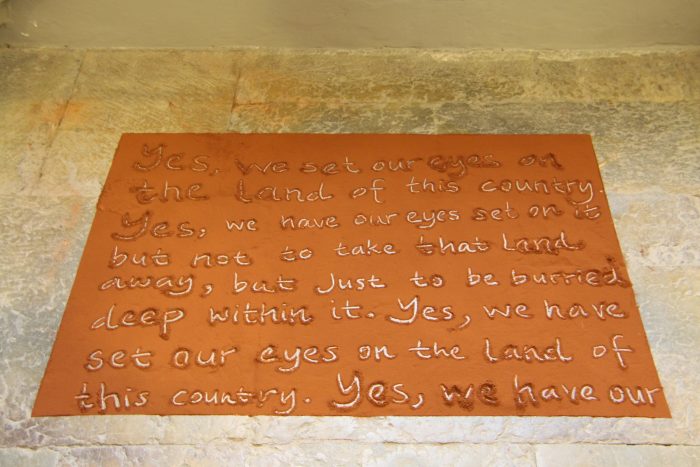

Didem Erk, Terrain to Trace, Installation, 2015

“Yes, we have set our eyes on the land of this country. Yes, we have our eyes set on it, but not to take that land away, but just to be buried deep within it!'”

Hrant Dink

Didem Erk, Two Close Peoples, Performative installation, 2017

Private and public

I and you

I and I

Romeo and Romeo

expatriated from the roots of oneself.

“Two close Peoples” is a site-specific performative installation, on the table sheet of paper is ready to transform into anything. Erk sees her body as a stylus and it is an attempt to problematize the boundary between language and body. To cover something sometimes makes it visible, to underline or to cross out a word makes it legible. How does the memory relate to performativity? Three books as a container of the wisdom of the world perform on the stage, and the stream of consciousness exposes the involuntary memory. Is it possible to remember with a troubled mind? Writing is a form of remembering and while one remembers it gets distorted. Like in a confession room, the thread of monologue alters to uncensored inner voice and forms itself with letters written to Hrant Dink. Mouth is filled up with words of an alphabet; the act of chewing book pages is as if keeping a secret of that silence. As a mobile storyteller reads the book aloud, if you hear it at that present time, it is there. Otherwise it gets lost. Pages are sewed word-by-word, sentence-by-sentence. “Two Close Peoples Two Distant Neighbours” is decomposed into inside and outside, that is the content and the cover. The act obliterates the legibility but it connects the thread of writing and thread of sewing. The needle operates an invisible violence working through by giving voice to the speech. The table invites a potential engagement of the possible attendant as a public labour to avoid the limitations of language, memory and body.

Over the course of the past two years, the living conditions in Diyarbakır have changed drastically and relentlessly. These changes had a strong impact on the production of the works, and a number of extreme events transformed the outcomes: The curfew that started after 6-7 October 2014 conflicts, during which tens of people lost their lives, incessant clashes, constant sound of explosions and gunfire, the attempt of a military coup d’état, the imposition of the state of emergency, the laying off of thousands of teachers. These and many other factors affected life in the city directly, and at the same time the process of preparing these particular works by the artist shown at this exhibition.

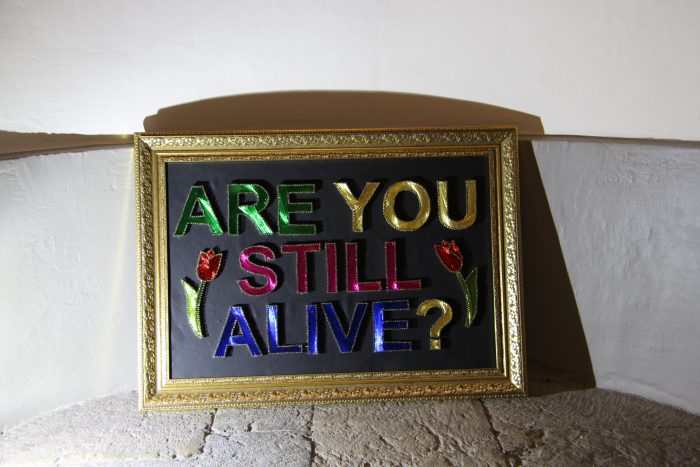

Berat Işık, Are You Still Alive?, Mixed media, 2016

Inspired by the Japanese conceptual artist On Kawara’s work “I am Still Alive”, which involves 900 telegrams sent to colleagues and friends, the title refers to the city of Diyarbakır and its hinterland, and the lack of communication between those inhabiting it and the rest of the world.

The title Are You Still Alive? also refers to a work the artist had planned to produce together with inmates of Diyarbakır Prison. Since the crafts workshops carried out with prisoners are cancelled due to the state of emergency, the project was completed by a crafts instructor in Istanbul, using a peculiar handicraft technique known as pin and thread art that is often used by prisoners in the region. An unknown inquirer poses an ambiguous question, one that so often appears in peoples’ minds after yet another explosion has taken place: By being led to think about his or her beloved ones, the beholder is induced to share that deep feeling of insecurity so painfully familiar to the people of the Diyarbakır region, both inside and outside of prisons.

Three video works titled “Dream” “Press” and “We Are Almost There” create a language from an abstract expression – inspired by John Cage’s renowned work “4’33””– to be able to convey the impact of political oppression on language and speech.

Berat Işık, Dream Video, 2016

“Dream” let’s the viewer to witness the aftermath of the livelihood of a slaughtered animal, where the nerves are in transition between life and death. This particular moment points out the residues of the life that was forcibly ended by human beings. Indicating the politics of flesh, where human being, position himself ahead of the food chain, claiming power on the bodies of the other, the film silently captures the final ritual of the body in its own rhythm.

Berat Işık, We Are Almost There, Videos, 2016

“We Are Almost There” is comprised of the footage the artist has recorded while crossing the Baltic Sea during his recent visit to Northern Europe, and citation of the 14th verse of Mehmed Uzun’s poem “Destana Egîdekî” by Ciwan Haco. In 1976 Mehmed Uzun had to make presumably a similar journey to Sweden to live in exile. The words of the poem are distorted to be unintelligible; referring to Uzun’s trials in which one of the military prosecutors insisted that Kurdish language did not exist. “We Are Almost There” relates to the language’s rough journey with a vague ending, in order to exist.

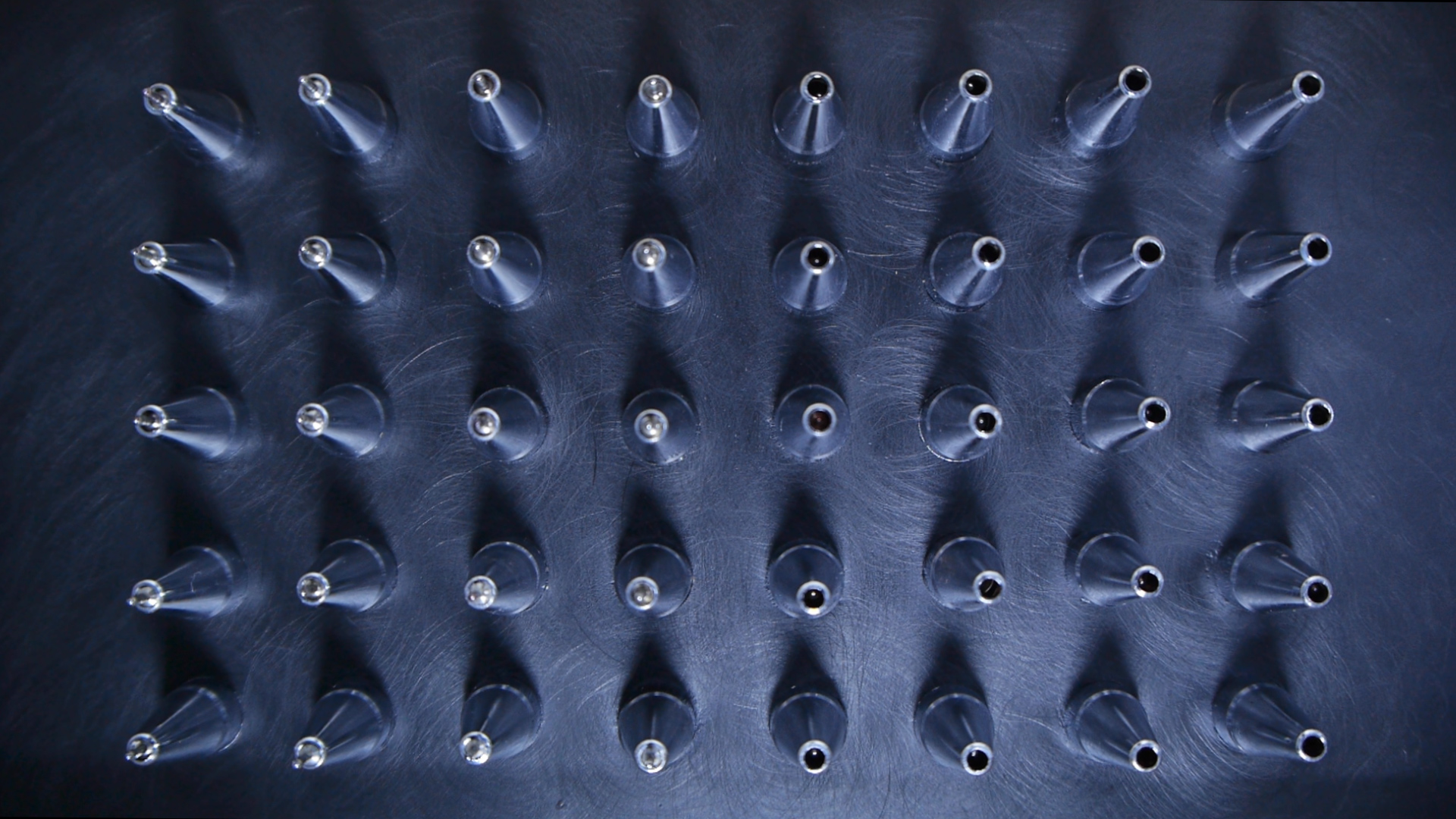

Berat Işık, Press, Videos, 2016

The work “Press”, has references to several meanings of the term press, from media to printing; from force to suppression. It narrates the silenced critical voices within the press as well as the loud and biased media.

“Dream” depicts the flesh, carrying the residue of once being alive, living unconsciously, showing the most obvious sign of life: heart beats. A poetic, yet disturbing moment between life and death, a silent transition at the slaughter house under the ruling regime of the humankind.

Berat Işık, Perfect Lovers, Mixed media installation, 2016

The work “Perfect Lovers”, citing Felix Gonzales-Torres’ “Untitled (Perfect Lovers)” (1987-1990), depicts a knife that is cruelly stabbed into the hope of coexistence in synchrony.

Zeyno Pekünlü, Father of all Fathers, Site-specific Installation, 2012/16

Father of all Fathers is a site-specific installation, A systematically composed listing of “affective” words used during Atatürk’s 1927 Parliamentary speech The Nutuk, which lasted six hours a day for six days. Pekünlü’s personal word selection from this vast resource frees The Nutuk from its own narration and shifts its focus, via the emotional content, from the real intention of the official ideology.

Zeyno Pekünlü, At the Edge of All Possibles, Lecture/Performance, 2014

“In his essay titled The Storyteller (1936), Walter Benjamin observes that he encounters storytellers less and less, claiming that information has superseded experience in the modern world. After 78 years, after the best and worst days of our lives, after a great resistance wherein many emotions have obtained new meanings, we found ourselves standing before a giant archive of analysis, texts, videos and images.

“How to represent resistance or uprisings in an artistic field?” is an ongoing discussion since 2000’s and there are a variety of trials around the subject. After the Gezi Uprising, we found ourselves engaged with the same question as well, in an increasing pace. Yet, personally, I was reflecting upon a possible “lack” by asking: “In this era of excessive information, is there anything left not represented?”; Could this lack be the “epic side of the truth” (as Benjamin defined), the human story, emotions, and affects?

In this lecture performance, I would like to try going back to the basics of story telling where the storyteller builds a story to preserve and spread the shared human experience: a story that anyone can connect without knowing the facts or where the events took place and the chronology; a story that can only exist within something bigger than one’s existence, only in a moment in which the body and the self dissolve in the body of the resistance, in which there is no “I”, and “we” changes its meaning. The sole tool of the story would be the oldest tool of mankind’s experience sharing: the human voice.”

PRESS:

Voice Inspiration, Austria, 4 April, 2017

Mema TV, Austria, 4 April 2017

Istanbul Art News, April, 2017

Steirische Kultur April/May 2017