L’ALBA di DOMANI

L’ALBA DI DOMANI / THE DOWN OF TOMORROW

SELECTED CONTEMPORARY ARTWORK FROM ITALIAN COLLECTIONS

Proje 4L/Elgiz Museum of Contemporary Art

MARCH – JUNE 2008

Artists:

Vanessa Beecroft | Letizia Cariello | Loris Cecchini | Paolo Chiasera | Cuoghi Corsello | Flavio Favelli | Fausto Gilberti | Francesco Jodice | Adrian Paci | Antonio Riello | Vedovamazzei | Francesco Vezzoli

Curators:

Isin Önol & Dr. Vittorio Urbani

The Dawn of Tomorrow* Hope as working tool in Contemporary Italian Art

There is a certain fairy tale in which a capricious princess, after many other wearisome trials, asks the knight seeking her hand in marriage, to procure a “gown the colour of time”, the classical impossible task. Perhaps one should ask oneself if this was not in fact just an elegant way to refuse the proposal. And yet, after many dangerous adventures this gown will be procured as proof that in real love nothing is impossible. Of little importance which colour this is in fact – it is, precisely, the colour of impossible and also it is the lack of it which renders incomplete any chromatic spectrum. Rare are the occasions that I have had the pleasure of being able to work on an exhibition with so much time in hand. Time to “try and try again”; to think, to choose and to change that which had already been decided. The luxury of time is the greatest of all luxuries. It has been important to be able to allow this project to settle, to give it at least a little, as they say in the fairy tale, of the colour of time.

The exhibition in March 2008 of the works of Italian artists originating from collections of Italian contemporary art at the Proje4L/Museo Elgiz in Istanbul, is a project born of conversations with Sevda and Can Elgiz back in 2006. Given the status of the Elgiz Museum as the site of a private collection, the brief I was given was to create an exhibition which would be an opening to the exchange of the Museum’s own collection with those of Italian collectors. They were interested in understanding the reasoning behind the choices made by the collectionists: why that choice in particular. And with this, to suggest to the entrepreneurial world, a world totally taken up with “doing”, an example of that which is possible to do with art and with artists. To analyse the working method of the collectionist, means having to focus on a central figure in the fragile world of art in countries such as Turkey and Italy where the public intervention of financing the production of contemporary art is desultory, not planned according to scientific and reproducible criteria, and in final analysis, totally insufficient. In both these Mediterranean countries it is a fact that there is an almost total organizational lack of the promotion and consacration of new art such as that which should be carried out in a network of museums. Whilst in the countries of north-west Europe and North America there seems to be a more linear ascending process of Artist-Gallery-Collectionist-Museum-Society, a coherent and transparent route – even if not entirely artless – of the affirmation of the value and the cultural historicizing of the artist.

The collector represents in this system however, the hub and the almost exclusive financier of the foundations, that is to say of the artist and of the gallerist. If in Turkey as in Italy (and somewhere else) the collector with his choices is no doubt an important cornerstone of the system, up to what point can he be considered a necessary and able delegate to substitute an inadequate public client? What’s more, is it acceptable that a private individual claims the right to such a task? And does the result in terms of quality, impartiality and the inclusion of the presentation of a certain cultural scene, come up to our expectations? Up to what point can we accept that contemporary “taste” with its continual return to the perception and modelling of the “spirit of time” and lastly, to the very history of culture, becomes influenced by private choices, however generous and disinterested in their intentions these may be?

In recent years on the visual culture scene in Italy and Turkey some big operators have appeared who cannot exactly be identified with the traditional figure of the private collector in his usual form – that of an individual or a high ranking family with access to supernational means of information. My intention is to speak with regard to Italy, of the appearance of “great names” such as the Trussardi Foundation, Prada, Teseco whose cultural production is often correlated and principally intended for the promotion of their own industrial project which in turn is that which produces the wealth then partially invested in art. Turkey, on the other hand, has seen in the last 10 years or so, the appearance of important financial initiatives from the banking and insurance sectors: Yapi Kredi Sanat Galerisi, Garanti Platform are just a couple of the more respected examples.

Another phenomenon which the two countries have in common is the establishment of important and ambitious private collections of contemporary art as out and out activities destined for the general public, equipped with new buildings endowed with all the characteristics of a museum: the Re Rebaudengo Sandretto Foundation of Turin and Morra of Naples, to name only two in Italy: and the Elgiz Collection in Turkey. Not that in both countries other important collections are lacking, but those listed have the special and important characteristic to compensate for – usually with an elevated level of consciousness – an inadequate public service. Typical in fact, is the attention given to the “services” such as a shop, cafeteria, educational activities which are usual features of a public museum.

Under this profile, the private collections museum project covers a double competence as both the representation of that which we may call the “fragile scenes” of contemporary art, very much based on “here and now” and on the postponement to a future confirmation of cultural values which requires a great deal of time before being able to accede to a traditional museum representation – and also assuming with conscious pride the roles of management and organization of the art system which if the political-economic conditions of the two countries were different, would normally belong to a public museum subject. This kind of collector is not one who decorates his own home with exquisite objects, but a subject relatively independent in his financial and decisional possibilities who converses, even if from his private position (of which he is however proud) with society at large; a subject who puts at our disposal precious goods studiously collected and preserved to the detriment of other purchases or activities in a genuine spirit of altruistic service.

The positive consideration, on the whole, of this situation – the private collector as a substitute for the otherwise absent public service – cannot be separated from the pending judgement on the quality of the collected art, nor from the responsibility of the choices proposed, that for the very fact of being chosen exclude or hide other different possible choices. There is also, in the ambiguity of private collection aimed at the public, the temptation to establish rules – as opposed to seeking them – and to impose choices and not to propose them. A complicated situation of ambiguity between the intentions and achievements which however is saved on the basis of what we call “ethics”: that is to consider the “good” which just the “doing” brings in itself, the doing passionately and freely for others: in comparison with public activity often managed dustily or not at all.

Landing in Istanbul are works which in truth come – as in the spirit of the Elgiz commission – from the rooms of the private collectors – but also in response to the challenge of the ample and unhomely spaces of the Proje4L/Museo Elgiz – some of the works have been conceived for Istanbul and realised on commission by the collectors for this occasion. Thus works by Vanessa Beecroft, Letizia Cariello, Paolo Chiasera, Cuoghi Corsello (Monica Cuoghi and Claudio Corsello), Flavio Favelli, Francesco Jodice, Adrian Paci, Antonio Riello, Vedovamazzei (Stella Scala and Simeone Crispino) and Francesco Vezzoli are launched. Works of art conceived and realised elsewhere, which, be it for their reasons, for their original intentions trail an aura behind them. It remains to be seen if, in a totally different context this aura will be confirmed or contaminated, enriched with other meanings with which to reverberate. And this is one of the more exciting motives for setting up an exhibition: under different skies things become different. The art object (if it is valid ….!) does not remain opaque and indifferent, but is transformed.

The aims of this exhibition are first and foremost to render the relationships physically visible: the relationship of the collector with the artist and with his work; a relationship for the greater part mysterious and dependent on sensitivity, memory, cultural interests and more. Why is it that a certain line or colour, or a message carried by a certain work interests the Vicenza industrialist or the Turin dentist? This is a difficult fact to interpret … as also the whys and wherefores of how the ideas and desires of the commissioning client can influence the artist … facts we only hint at here, leaving further considerations to the exhibition visitor. What is more, here a relationship between the two countries, Italy and Turkey is mediated through the works, conceived and created in Italy, the country from which they come and to which they return. And finally, the exhibition offers a physical and conceptual terrain for the relationship, always rich in unpredictable results, between the works and the visitors.

This is not therefore a “curated” exhibition: our choices come after a first selection of artists proposed by their collectors. The curator has therefore found himself with a pack of cards in his hand with which he has had to play the game. Therefore a “do-it-yourself” exhibition? In a certain sense – in spite of our role as curators – we like to think so. It was created by means of a set of internal rules: in the same way as a game of cards, or like a storm.

Less obvious, on the other hand, is the examination of the scene which inevitably the works collected together in the exhibition suggest. An exhibition is an exhibition: the eye recognizes and associates; the mind elaborates again and constructs meanings. How can one avoid a generalized comment? What then is the common denominator of an non-curated-exhibition? What can he say, stepping back to observe and understand it, the unfortunate curator-non-curator? It seems that we can say that the value of the metaphor as an expressive instrument so much a second nature to Italian art is confirmed yet again: that the all-embracing language of media and expressive techniques of the last twenty years are always vital and alive; and that, what’s more a direct reference to social, political and ethical themes on which the artistic expression in Italy has been traditionally reticent, now appears here and there with fresh vitality. It seems to us too that a recurring theme is a faith in the word, in speaking through the artistic object: an optimistic hope in human communication.

Hope as an instrument of art … as a working tool. The hope to be able to gain and move limits: from time to time presented to us again by means of a suggestive thought that operates through the analysis of the different media of the art (as in the works of Vedovamazzei and Cuoghi Corsello), permeated with social-political Utopia (Chiasera), of a humorous criticism of the stupidity of established traditions and power (Riello), of loving and at the same time, critical comment on the stereotypes of fame and glamour passed by the mass media (Vezzoli, Beecroft), of disquieting domesticity and fragile, childlike assemblages (Cariello), to the misunderstanding of dialogues between different worlds (Paci), even aspiring to silence and to the sublime but without waivering an ethical judgement (Favelli). With this hope, fatigue and lightness, as in a great dance, are to be found the supposition and the outcome.

Another famous fairy tale challenges the power of the gurus and mandarins, telling us about the supposedly new clothes worn by a credulous monarch. “The King is nude!!” the laughing crowd shouts. In our organizational work for this exhibition there is a conscious critical behaviour and attack on the income of the established and maintained position held by curators within the world of contemporary art. Let’s go further down to explain.

We are at this point tempted (as mentioned above) to study with attention and to throw ourselves passionately into the unusual form of this exhibition as a model of a non-curated exhibition. Are curators really still necessary? Had not humanity lived more or less well for several thousand years of honourable social culture without ever having felt the need for this intermediary figure? And lastly, if the truth be known, are we not all truly fed up with the figure of the “UberKurator”? Of the band of dandies who invite one another hopping from one biennale to another, imagining projects which are as fantastic as they are unquantifiable and craftily weightless in terms of real production and management, the choice of which will always naturally be declared not conditioned by the logic of the market? It is always a bit strange to consider how short lived strategies and wiliness manage to earn cosmopolitan successes.

After having discussed how this is an exhibition, at least from a non-curated point of view with regard to how a “do-it-yourself” exhibition should be – in spite of the fact of following its own internal rules – we are interested in asking ourselves nonetheless, if a message, a common meaning comes across. We believe that a factor common to all the works in the Elgiz museum is that of hope: hope as a working instrument, literally as a tool to create art in Italy today. What induces us to speak of hope? To the everyday problems respond the action, the flow of things and of the works. Hope is the energy which permits this flow. Even the most subtle and lyrical art is inevitably linked with the “doing” and the duty to transform the idea into something. It is the fascinating and uncertain process by which the idea is launched through what can sometimes be painful effort. It is work as a reassuring daily practice (like a prayer) which induces us to hope, or is it the work itself as a constructive process (which overcomes nullity) that saves hope? The works chosen by the collectors aim to show the recent Italian scene: the oldest is from 1994, many from 2008, and some even created for the occasion of the Istanbul exhibition.

Vanessa Beecroft (Genova, 1969) in the work VB54, YFK Airport, New York (2004) from the UniCredit Group Collection, presents a contradictory image. Beneath the shining surface of a publicity image, a group of nude models are standing, perfectly still, in a space of a corporate nature. It is an “action” at the Kennedy Airport of New York – but an action with no practical outcome, therefore, in itself contradictory. We are used to reading an image as testimony to a fact: but if the action is the end in itself, orchestrated by a director who hides his intentions, the image we see seems to refuse its own documentary value. It is difficult to say what has happened: the indifferent models lined up like extras front stage at the end of a show, seem to witness a state of arrival, of emptiness, maybe ready to agree to completely different sets of values. The nude women, apparently devoid of emotions too, stand balanced on their stiletto heels between an extremely dispossessed condition and that of mysterious power, conferred on them by the world of fashion and of publicity for which they seem to have been born. From the Cilluffo Chianale Collection of Turin comes VB02, one of Beecroft’s first works dating back to 1994.

PRESS

June/August 2008, Arte e Critica: “L’alba di domani. Arte contemporanea, Arte e Critica“, n.°55 pag. 118, by Rossella Moratto (Italian)

April 2, 2008, Arkitera: “Koleksiyoncuların Sergisi” by Ahu Antmen (Turkish)

March 26, 2008, Exibart: “L’arte contemporanea italiana è protagonista in Turchia” (Italian)

March 12, 2008, MAMe: “Un Dialogo: Italia – Turchia” (Italian)

Letizia Cariello (Copparo, 1963) sews and sows signs and numbers into her works. To sew…….. to put pieces together, a woman’s gesture for thousands of years: to sow, that is to believe in the future growth of things which are nurtured and loved. Often employing embroidery, Cariello draws an agenda so as not to forget. Are those numbers shopping lists repeated in rather unsteady rows? Calendars to remind her of a visit to the dentist or of a meeting with someone really special? Sleeping Bag for a Little Kamikaze of 2008: there are objects that come from the room of her own children sewn onto the little woollen dress of the child. Objects therefore (also less innocent like the little plastic hand bomb from which the work takes its title) which are part of the everyday life of the artist’s family, that being transformed into art become fixed and consigned to memory. They assume a more generic and altogether more universal meaning. And in this way they are saved. The Valentinis Collection presents the works of Cariello. Hope emerges again in a small, seemingly ephemereal work: Fly in The Glass of 2008. A perfectly normal pub-like glass upturned traps a fly as if with the intention to free the fly without killing it: in actual fact a sheet of paper is slipped under the glass almost as if the fly is about to be released to fly out of the window. But the fly, which appears real to us through the refracted glass, is only drawn on the paper, and as such, the fly is no longer an insect, but becomes art: almost a Baroque joke.

The Tomei Collection presents the work of Paolo Chiasera (Bologna, 1978). Chiasera has very much a masculine Creator approach: the world is the field for the feats of heroes, true or false these idols is of little importance. A recent work renders monumental the figure of an idol of young culture, the rap singer Tupac Shakur, murdered prematurely in gang warfare, making a tribute of a statue to him, normally assigned to the pure Risorgimento Hero. In his work displayed at the Elgiz Museum Chiasera takes on yet again the cultural and idealogical references to the system which a young person has to face up to, in the complex project Young Dictators Village of 2004. Nine of the artist’s friends squat in abandoned rural buildings with flags, slogans and large portraits of controversial idols of the twentieth century: from Mussolini to Pol-Pot, from Saddam Hussein to Mao Tse Tung. Half way between a Boy Scout camp, intent on playing role games, and an illegal paramilitary exercise. Running lightly on the dangerous brink which divides a serious cultural and political commitment from an indifferent and cheerful qualunquismo, at the end Chiasera makes a call to arms for a commitment, unrolls a flag to keep high the ardent vitue of the young mind, that giving of body and soul to the party which each of us must engage with the grand causes of life. If this is not called hope…

The duo Cuoghi Corsello (Monica Cuoghi, Sermide 1965; Claudio Corsello, Bologna, 1964) is the proposal put forward by the Tomasinelli Collection. Suf/Istanbul is a very recent work: a wide and soft “graffiti” transformed into a three-dimensional sculpture in wood. Graffiti are part of the chromosomes of the experience of Cuoghi Corsello. A gesture belonging to the young marginal world which silently slips smoothly like a snake into the world of art, confirmer of meanings par excellence. Then three large wooden Xs leaning against the wall … XXX of 1999 an ambiguous and mimetic work in all its apparent graphical innocence as an object of minimal design (maybe a new kind of clothes hook?). But currents of different meaning become caught on the three X as on hooks. Their just being sufficient to themselves, tipped and leaning like that against the wall, seemingly temporary but in reality more stable than as if they were in an upright position. Then the lack of any signs or symbols which would make them recognizable as being marketing or idealogical (they are after all crosses of Saint Andrew). Lastly, the lack of colour, maintaining the apparently neutral “wooden” colour that is – precisely – that of the natural material with which they are made. Why then, three, and not one only or twenty-seven? Is it perhaps the perfect three of the trinity? Sometimes when one asks a child the reasons for his way of playing or for something that he is building, the reply will be a hurried “just because” or “because it’s beautiful like that” … .is this a refusal or just a shyness to explain himself? Thus XXX makes us think, yet again, that the best art is that which maintains a good dose of the arrogantly inexplicable.

With Pavimento3 created in 2008 for the Istanbul exhibition, Flavio Favelli (Florence, 1967) puts life back into used materials, in part exploiting them beyond their original “intention”. Wooden planks from a Turkish building site become a vaguely stylish podium, or perhaps only the floor of a suburban villa in the Bolognese Appenines. It is, therefore, a platform for looking around, to be higher than before, to see further and better into the landscape and perhaps inside ourselves. Reused railings from who knows which stationside villa balcony or house inhabited by elderly spinsters are now the triumphal lookout of Casa Golinelli in Bologna. With Belvedere of 2005, Favelli grafts the work of art onto an architectural construction, but the installation throughout seems to withdraw from the haughty status of the “work of art” to be reabsorbed into the calmness of a home. Hope for Favelli is to be found precisely in his constructive doing, in compassionately giving back a meaning to objects which, having lost their memory, had lost their significance. In the giving with faint irony new configurations to objects already given and characterized, Favelli demonstrates faith in the transformative and saving power of fantasy.

Francesco Jodice (Naples, 1967) is proposed by the Art Collection of the Unicredit Group. The artist doesn’t transform but renders complex the representation of reality. A photographer who feels harnessed by the unvanquished ingenuity of the camera, the way of Jodice is to tell what goes on behind the photograph, sometimes through large shots of inhumane monumental architecture, other times shots taken from everyday life. On show are Tokyo (Series What We Want), Bangkok (Series What We Want) and Sao Paolo City Tellers, the first two being large enigmatic images of the city; the third is the map, almost the project for the homonymous film. Some photographs of Jodice seem to come from photographers with different interests: but their common fabric is the faith in the healing power of the story. It’s as if he says to us … “look at this again … wait while I explain better”. In the series of photographs in which he follows a character along the streets, without his knowing, shooting various images of a somewhat common daily life, there is adventurous fascination to ask oneself “what will happen now” garnished with the sincere and melancholy eroticism of the stalker. Why is “he” turning right now instead of going straight on? Coming face to face with the life of the other – neighbours, son, lover, work colleague – we turn a vivisectional and relentless eye towards the mysteries of our own same actions. Why … ? Jodice precisely for this request for further comment, for this vital desire to distance himself from absolute and presumed one way reading of the photographed image, often resorts to a series and also to the video instead of the film as in the recent Sao Paulo City Tellers of 2006 also present in the exhibition.

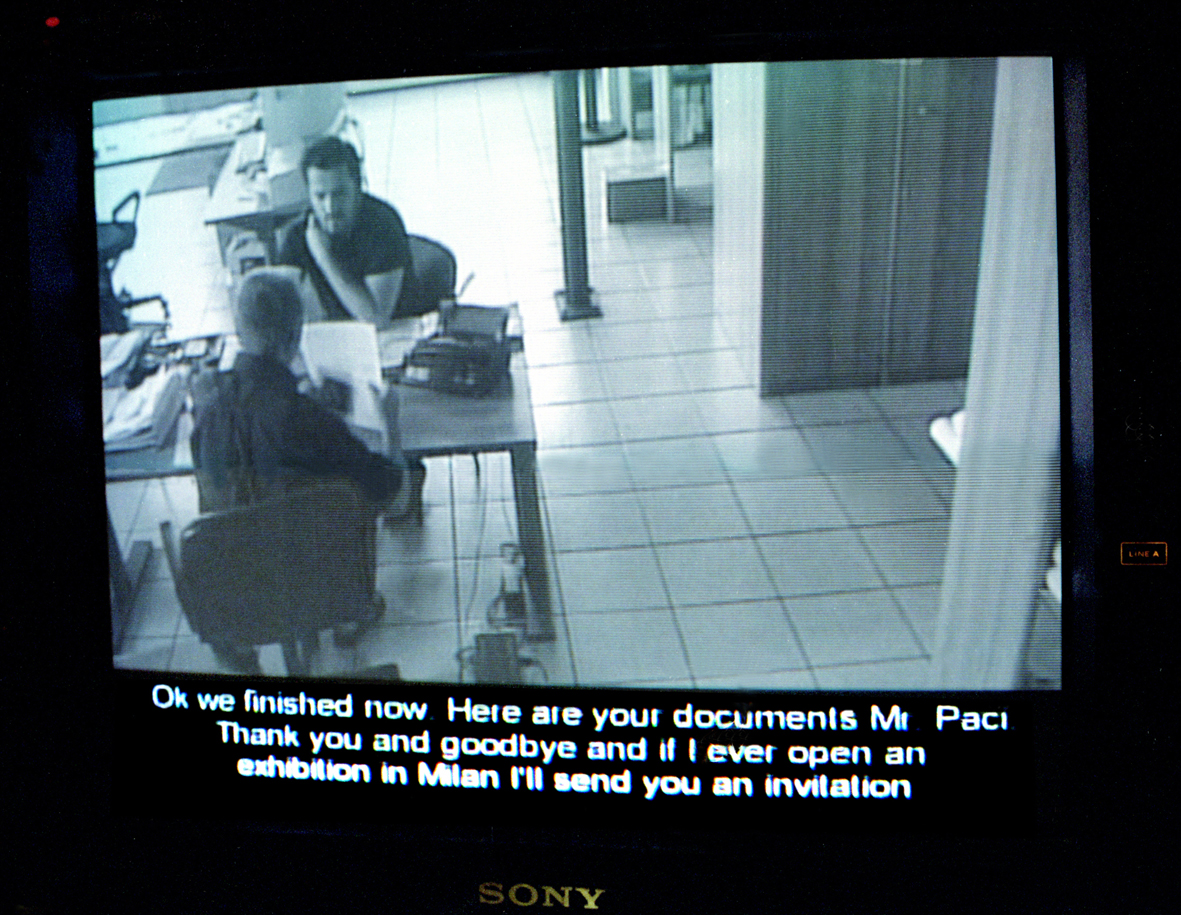

Adrian Paci (Scutari, 1969) seems to believe in light as a visual representation of hope, and perhaps of the absolute. In the video works Turn On of 2004 (in an abandoned factory men turn on a lamp each, using noisy portable electric generators) or again Per Speculum of 2007 (children nested in a majestic oak tree make the sun shine against the lens of a web cam filming the scene by reflecting it on mirrors) lights guide, lights dazzle. Paci immigrated from Albania to Italy, and from this personal experience carries the naturalness of the hope and of the freshness of visual observation of one who has fitted into a society of a foreign formation to him. The exhibited video Believe me, I am an Artist is on the other hand, a work which is really scarce in lights. In the grey/blue of a security camera, we see the reconstruction of a scene which really happened to the artist: in a small room of the Italian customs an officer investigates into the reasons that Paci has for carrying with him photographs of his nude daughters. In an embarrased and fragmentary dialogue unravels between the officer and the artist. The idea that the photographs are “art” seems to be difficult to comprehend for the customs’ officer (face invisible, almost an omnipotent kafkanian inquisitor of the Castle) for whom they present a more terribly commonplace probability of being pedo-pornographic material. The hope of the immigrant – and of the artist who is always an immigrant in daily life – is faced with the bitter reality of diffidence and disillusion. The participation of Paci is proposed by the ACACIA Association Collection.

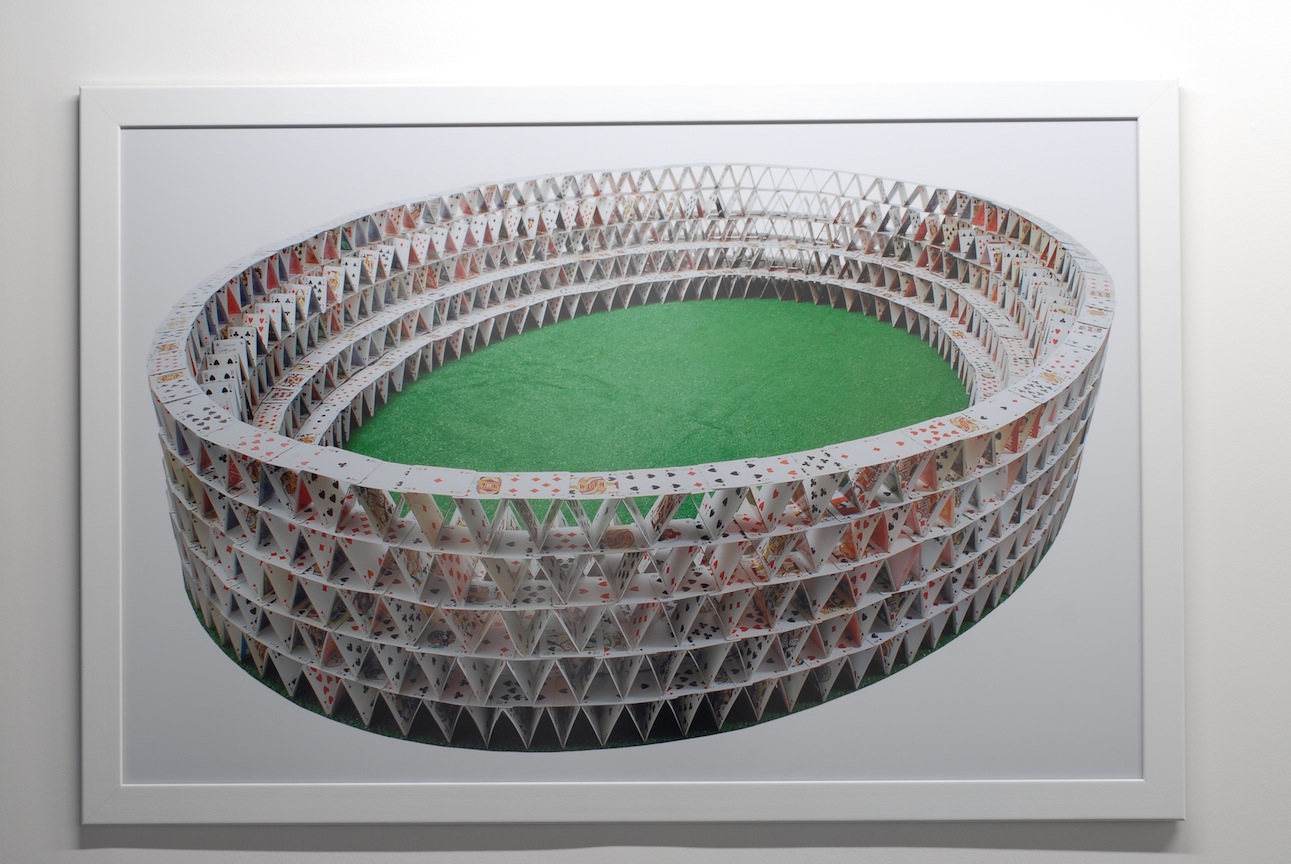

Antonio Riello (Bassano 1958) has an aeroplane fly to Istanbul Benedetto’s Tactical Fighter of 2005, the large and exact model of a military aeroplane decorated with the arms of Pope Benedict XVI and figures of angels and saints like a frescoed ceiling. Only recently the Vatican has abandoned the death penalty, and beyond the perpetual and stereotype calls to Peace, it commits itself with evident relish to the wall against wall of integralism. Ambiguously, it represents the ancient problem of the relationship between spiritual and temporal power. With childish but false ingenuity Riello seems to propose: here are the Pope’s war planes. The bellicose device contains in itself the paradox of the “all Italian” beauty of the decoration linked intimately with the objective inhumanity of the function. From the Forin Collection of Vicenza. The large photograph A Desperate Attempt of Vice to Become Virtue (2006) shows us a large “colosseum” of playing cards. Taking those which were real playing cards from a casino and transforming them into architecture, the artist almost, by means of a short circuit, illustrates the very title of the work. which smacks of a popular proverb. Another photographic work, the installation Politburo (2007) presents us with the the unmoved and most registered faces of the last Soviet Politburo … the artist uses actual photographs of the officials taken from historic materiaL … though they are anonymous grey men for us now (but for the young and recognizable Gorbachev). Again a work on power – presented through its official and public image as a seal of consolidated values. Popular cultural models are often utilized by Riello as his work table. Dissecting the banality and often also the insincerity, Riello leads a lucid critical discourse on the interests that lie behind such presumed “values”. In an exhibition a few years ago, yet again in Istanbul (Borusan Sanat Galerisi) Riello had constructed a faithful replica of the iconic tower of Galata, made with hundreds of cubes of sugar with the top of the tower made golden by the use of chocolate wrappers. In the amused smile of the visitors to the exhibition at finding an important symbol of the city, the pleasure of recognizing the monument merged with the surprise at the inadequate representation by a domestic and not an artistic means.

Vedovamazzei (Stella Scala, Naples 1964; Simeone Crispino, Frattaminore 1962) take on again the theme of hope in a constructive and optimistic mode. They Want To Be Famous is a new work being created just as I write this text, specially for the exhibition in Istanbul and in this city. A generous contribution to the exhibition by the Collection Corinaldi. A modern neo-Baroque divan bought at the Bazaar is covered with gold material. The splendid surface of the fabric carries the scratched title of the work itself, which allows the light from inside the furniture to peek through. An object with a double nature, that seen from the front is a piece of really kitsch furniture, from behind on the other hand, it becomes text which one attempts to read at varying levels. Often the apparently casual assemblage of their work of old furniture and objects creates momentary settings and fictitious familiarity in contradiction with the biographical status of the materials used which come from other stories and other drowned paths of other lives. RGB (from 2003 but here recreated for the Elgiz museum) is a fascinating childish action on the part of the Neopolitan duo. Starting from an imaginary starting line, twenty or so coloured adhesive tapes of varying aspect, colour and function are unrolled and create a sort of “bar code” on the floor.. Another work is Cumshot (2008), 28 collages on paper imitate oil painting and its characteristic thick dripping – even if the embarrassing title alludes, with a stroke of the intellectual vivaciousness characteristic of Vedovamazzei, to a very different context.

Francesco Vezzoli (Brescia, 1971) mixes elements of popular culture (in the sense of pop) in representing the face of the stars of the cinema he conveys the illusion of sharing their destiny and perhaps the fame. But the movie stars get old and leave the scene, the world rapidly consumes their image and ephemeral fame. Vezzoli uses expressive methods (in Burt Lancaster like Mario Praz from the Cilluffo Chianale Collection) just as in the traditional female world such as embroidery; a medium which, in itself contains the sentiment of the time needed to produce it, the long periods of female domestic solitude. Embroidery – in its turn – takes us to decoration … a word that is taboo in modern visual culture; and perhaps also takes us back to the involuntary controversial flavour of that “made by hand”, to the uneconomic employment of time: other concepts in contrast with the methods and timing of the present day production. Vezzoli, this very Italian artist, also proposes a research into the sense of Beautiful as a category: the truly ancient tension and typical of Italian art, towards Beauty as Perfection in the ethical sense too.

Springing from a fairly linear idea of an exhibition “chosen” by the collectors, by means of a curator selection from the initial proposals of the collectors, one arrives at a problematic but interesting situation in which different selection processes are superimposed without fear of entering into contradiction between one another, and a paradoxical – but open and unconventional – “choice/non-choice”. We believe and desire that this should be a conscious attack on the dictatorship of the curators in force right now. Instead of freeing the artist from the grips of the market and the restricted historical prospects of the Museum, the international curator has put into movement – even if unintentionally – a machine working above all for his own self-promotion. Maybe a new front and a new organizational model can emerge where the model of work no longer runs the usual roads and above all, knows how to be impervious to the consolidated hierarchy and to not respect the established “modus operandi”. We believe that it is from different working systems and different productions such as this erected for the selection and the production of the exhibition for Proje4L/Museo Elgiz that new indications of procedure and critique may emerge and open new prospects of freedom.

Taking art and artists to another country is a little like taking a gift. Gifts are not always altogether innocuous: they divert the desire of the donor, and require certain obbligations from the recipient. An exhibition is certainly many things: and amongst these maybe also the Trojan Horse. Let us hope, however, a “good” Trojan Horse, that is to say a container steeped in meanings which may find themselves in contradiction with the place and person that receives them, to be therefore in some way “dangerous” but in a positive, joyful and fertile way.

I dedicate my thoughts for this exhibition to my very beloved friend and teacher Beral Madra.

Vittorio Urbani

* title of a song by Tiromancino, 2007: “…and if it does not frighten you, you will be able to see my nature: the dawn of tomorrows………”

L’ALBA DI DOMANI / THE DAWN OF TOMORROW

L’ALBA DI DOMANI / THE DAWN OF TOMORROW

Held in Istanbul at Proje4L / Elgiz Museum of Contemporary Art

March 26 – June 6, 2008

On show works by:

Vanessa Beecroft

Letizia Cariello

Loris Cechini

Paolo Chiasera

Cuoghi Corsello

Flavio Favelli

Fausto Gilberti

Francesco Jodice

Adrian Paci

Antonio Riello

Vedovamazzei

Francesco Vezzoli

From the collections:

Associazione ACACIA

Cilluffo-Chianale

Laura & Mauro Corinaldi

Elgiz Collection

Marcello Forin

Marino Golinelli

Vezio Tomasinelli

Warly & Robert Tomei

Unicredit Group

Alessandro Valentinis

Show curated by

Vittorio Urbani

Işın Önol

With collaboration in Venice and Istanbul by

Lorenza Savini

Murat Özelmas

The show has been produced by Proje4L-Elgiz Museum of Contemporary Art in the frame of the series of exchanges of international private collections

Supporters

Italian Collections, Italian Embassy Ankara; Italian Cultural Center, Istanbul; Turkish Airlines and Nuova Icona Venice

Logistics in Venice by Nuova Icona

Responsible for sponsorships and communication Media Arts srl, Milano

The curators and Elgiz Museum want especially thank to Marco Biasini, Marco Ferraris, Francesca Kaufmann, Gio Marconi, Neve Mazzoleni, Massimo Minini, Franco Noero, Pier Maria Riccardi, Glores Sandri, Catterina Seia, Binnaz Tukin, Marinella Venanzi, Angela Vettese

Catalogue design

Ahmet Öktem, Istanbul

Texts

Sevda Elgiz

Vittorio Urbani

Turkish Proof Readings

Brunilda Pali,

Binnaz Tukin

Italian Proof Readings Vittorio Urbani

English Proof Readings Janys Hyde

Photographs

Vittorio Urbani (portraits Cariello, Jodice,Vedovamazzei),

Matthias Vriens (portrait Vezzoli)

Jennifer Livingston (portrait Beecroft )

Ahmet Öktem (artworks)