SERIOUSLY IRONIC: POSITIONS IN TURKISH CONTEMPORARY ART SCENE

JUN – AUG, 2009

SERIOUSLY IRONIC: POSITIONS IN TURKISH CONTEMPORARY ART SCENE

Centre Pasquart, Biel, Switzerland

Artists:

Erdag Aksel | Selda Asal | Selim Birsel | Nezaket Ekici | Leyla Gediz| Sakir Gokcebag | Gözde Ilkin | Devrim Kadirbeyoglu | Ferhat Özgür | Serkan Ozkaya | Hayal Pozanti | Hale Tenger | Muruvvet Turkyilmaz | Hande Varsat

Curators:

Dolores Denaro & Isin Önol

website of the event

PRESS

ARTISTS:

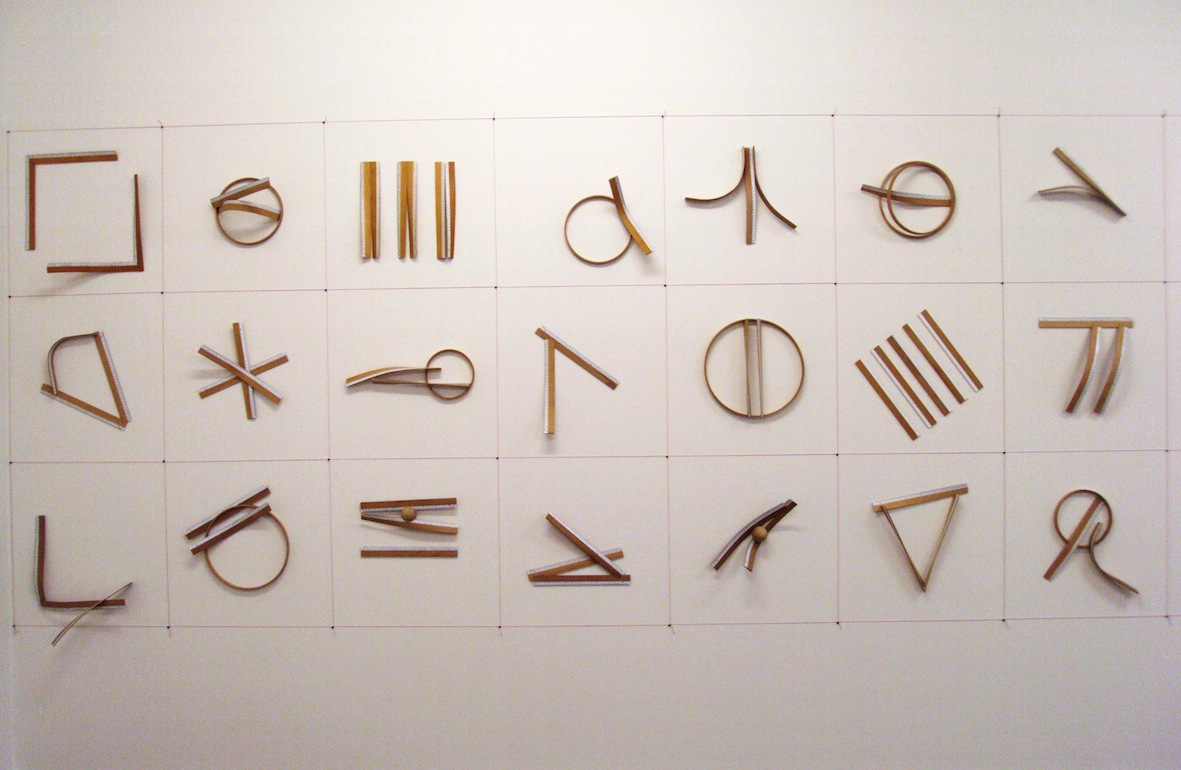

If every artist has an obsession, Erdag Aksel’s is thinking. He can perhaps be better described more as a thinker than as an artist. Once described as “critical critic” by his wife, theoretician Ayse Kadioglu, it is no coincidence that his recent works have been concerned with an object like ruler.

For many years, Aksel was very interested in creating series of objects that could not easily be described as either sculptures or pieces of an installation. Although the main effect was more of a sculpture, and the artist has constantly been defined as a sculptor, these objects do not actually fit the simple definition of sculpture. Moreover, he was not trained as a sculptor but has found himself working obsessively with objects.

Aksel started working with objects in mid 80’s, after a military coup in Turkey where tension existed at every aspect of life. As a consequence of this his first series was titled Objects of Tension. His first intention was formal as had the interest in the physical tension created by playing with balance, fragility, weight of objects. But then his interest in the idea of tension became more political and conceptual. It was a time when many people were being arrested and held in custody for political reasons, and people were therefore nervous about receiving unexpected midnight calls. Wearing neckties was considered one of the signs of whether one was for or against either Europeanism or Islamism. The flag was also a big symbol in terms of militarism and nationalism. These kinds of symbol objects such as flag, telephone, necktie, thus became a part of Aksel’s work. Ironically, after thirty years even in today’s Turkey, these objects may still be the cause of a remarkable tension.

His second series of objects was called Objects of Hesitation, exhibited in the early 2000s. He collected many objects of personal interest as well as symbolising violence and war and exhibited them in large picklejars on stands that seemed insecure and unbalanced. Last year, the last part of series was exhibited under the title Objects of Beauty.

The ideas of the flag and rulers seemed to have merged in recent years in Aksel’s work and he started creating sculptural forms of flags out of rulers. More recently, the rulers began constituting an invented alphabet. A Calculated Loss of Memory III, taking place in Seriously Ironic, was created very recently. It is very different from his typical work in a formal aspect but conceptually it may be considered a conclusion of what the artist has done so far with flags. He represents an invented alphabet by simply bending and pasting traditional 30 cm. wooden rulers used in the secondary school system.

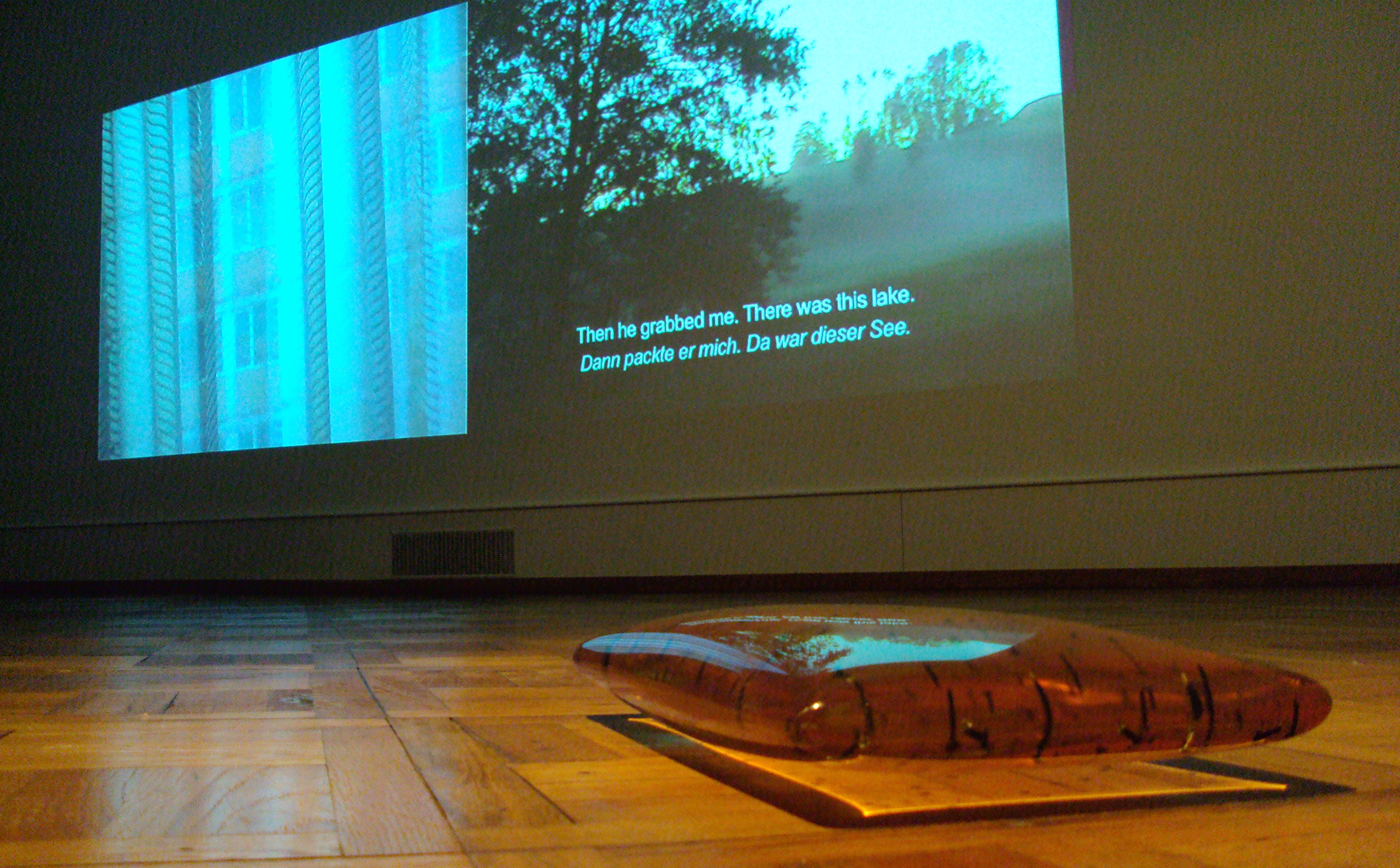

Selda Asal, in her video installation series of Restoring hope investigates the connection between the sentiment of “hope” and holding on to one’s own existence. She points out the thin line between having hope and the moment of losing it. Every single video of the series creates similar questions in the viewer’s mind: Where does hope start and where does it end? What motivates it to exist or disappear? What happens when one loses it or regains it? Ironically, and sadly, the viewer is left with a feeling of hopelessness and powerlessness. They can only ignore what seems inevitable.

In this series of video installations, Selda Asal analyses the fact of suicide as the very thin line between death and life, and between having and losing hope. The series started with young girls who had attempted suicide, and young boys with drug addictions. It continued with following work, entitled Hard to Die, which is about the tragic stories of the women who have been forced into suicide by their own families in order to preserve their so-called “honour”. During the creation process of the entire series, Asal selected and visited several “restoration places” for hope, such as hospitals, clinics, various committees and for the last project, women’s shelters in many cities. She encountered the tragic stories about “honour-killings” at first hand and represented these stories through her artistic point of view.

Selda Asal realised this project in various cities and countries by individually interviewing several women most of whom were associated with women’s shelters. The video piece shown in Seriously Ironic entitled See Me… Who Was I for Real was shot in Sweden in 2008. The stories are told by women who are often forced into death with the consent of their families, and often after having experienced violence, rape and other sexual harassments. These women were actually some of the few survivors who have been able to run away from the trouble. They were strong enough to fight with the realities of their lives or weak enough not to commit the sin of killing themselves, as indicated by the religion. The people who are telling their stories are not clearly exposed, or recognisable, as they are still living under threat of being found and killed. Instead, we are shown their body gestures and the images that these women draw while telling us what has happened to them. As these images function as illustrations of their dreadful experiences, Selda Asal amplifies them by means of strong sound effects. The pain, fear, panic, suffering, and other similar sentiments are represented through this sound more than by the voices of the women, or by the content of their dreadful stories. The tension between the freedom of being a runaway and the paranoia of being caught again, and killed, is made palpable to the viewer.

Selim Birsel’s artistic production occurs in his personal journeys. He is a genuine collector of objects and very much interested in the memories of each object and what they represent. As the articulated memories constitute history, one could consider what Birsel does as ‘digging history’. He describes himself as a “flaneur” who regularly collects certain objects from streets.

He accumulates these objects and through their quantity and plurality, these objects start constituting their own messages. On the other hand, since all these objects had their memories, they are also abraded and diminished because of being used or thrown. Therefore these objects do not contain their stories through their plurality but their abrasion. Through their plurality, the objects only strengthen their stories. Considering his noteworthy seriousness in this quite awkward practice, I believe he fits the title Seriously Ironic of the exhibition the most.

Quietness can be a keyword for Birsel’s work and behind this quietness his works contain personal and political values. He has always produced installations that communicate deeply with the space of production. An obvious connection runs through all his works. For that reason, knowing his earlier works helps one to perceive his recent works better. In his last exhibition Backyard in Istanbul in 2009 he also produced a book to guide the viewer with his earlier works. Since most of the texts were written by him, the book becomes one of the works in the exhibition. Through this book, he viewer confronts the personal history of the artist through his narrative writing style. In this book he describes his way of looking back at his works through the word “introspective” and through that he summarises his last ten years of art production process. Because there are many words behind his works to be read by the viewer, for the people who have been encountering his works for many years, this book creates certain relieve.

The installation Table of Collected Memories was produced in Aley, Lebanon in 2008. A group of artist were invited to produce at a selected site and Birsel found himself re-organising the damaged and abandoned garden. He wanted to function as a landscape gardener and started clearing out the overgrown weeds. He collected every single object he found in the garden and in his “flânerie” (vagabondage) trips. Although he organised very nicely on the stone table of the garden, the objects, which had the memory of war, were very sad and meaningful. He completed the installation with the photographs of the garden he took in Aley and with the curtains made from the fabric he brought from Lebanon. Birsel’s tank-shaped stamps create a certain texture on the fabric of the curtain.

Born in Turkey in 1970, Nezaket Ekici moved to Germany at an early age and this cross- cultural background is reflected in her work. As a student of Marina Abramovic for both her BA and MFA degree, she demonstrates a high level of physical strength and forces the limits of her body in her performance.

Ekici has produced a large quantity of performances, each of them deeply thought through, well organized and strongly produced. In many of the performances she questions local values, religions, habits. She has produced numerous performances where she is stuck in certain circumstances and physically tries to get herself out of the situation. In most of her performances, we see her ironic approach to the generally accepted ideas of beauty. She uses beautiful dresses and make up, and sometimes decorates the environment with flowers, but during the performances she uses her entire power, sweating and screaming, without caring about how she looks.

Gravity is a twenty-minute-long video performance, prepared for the exhibition Mahrem in 2007 in Istanbul. “It shows the aesthetics and the dexterity needed to put on a veil,” Ekici explains. As has been the case in Turkey in the last couple of years, the issue of veil is being discussed in many countries from different aspects. Although veiling also exists in Christianity, Judaism and in many other religions, nowadays it is more of a symbol of Islam. Styles and notions of veiling differ in every Islamic country. In some Islamic traditions, women wear the burka, which is a further step from veiling using an enveloping outer garment for the purpose of cloaking the entire body. By continually putting numerous headscarfs on top of each other, Ekici’s performance indicates that there are no limits to the veiling of oneself. She exaggerates the ambition of one’s veiling to indicate the absurdity of doing so.

The subject matters that Gediz deal with vary from extremely personal to universal. She made numerous paintings departing from her personal memories and subjective perspective that are not perhaps solely comprehensible but still attractive. Through her paintings Gediz creates certain mystery by leaving the viewer with the unknown fact behind the subject. Rather than a narration, sh

e suggests a scene taken from memory without giving a clue for the former or latter scenes. The grounds behind the selected scene are left indefinite. As well as its subject matter, the motivation of the selected frame is kept hidden.

For Seriously Ironic, there are five paintings shown from Gediz, all oil on canvas. The selection opens up a possibility to see the fact that her techniques, touches and subject matters highly differ from one painting to another. Her representations of shadow are particularly strong and create partial illusions within the painting. This strength is clear in Key and Frontal. Her portraits, however, go beyond realism and reflect personalities, even though we might not know the owners of the faces. Nosebleed is one of these portraits. The event prior to the mysterious look and the reason behind the bleeding nose are kept secreted. The sadness of the circumstances that the figure is in and the pleased impression on the figure’s face occur simultaneously. The story of the moment is again left unclear for the viewer, perhaps not to solve, but simply to enjoy the scene. Leaving Nisantasi and Haight Street also leave the viewer in a similar kind of unidentified area, except the clearness of the fact that these scenes are selected from the very personal history of the artist.

In each painting of Gediz, the attention of the viewer is invited, and further, drawn into the unknown history of the selected moment. The strength in the realistic representation might ensure one that the scene is depicted from an actual event; however, this assurance does not facilitate an achievable indication for further interpretation.

Coming from a graphic design background, Gökcebag is extraordinarily precise in his work, and this is his strength. Making examinations of stitching on photography for a while, in late nineties, Gökcebag started working with installations. He selects some objects from daily life, starts creating a variety of installations with those objects and works with it until he has tried every single possibility with that artwork. Out of these installations, he creates digital-like images within the three-dimensional space. From his very early works up to now one clearly sees the consistency in his artistic path.

Gökcebag keeps his selection of objects limited. His work is more about the possible varieties and arrangements that he creates out of these objects. By cutting the objects in pieces and bringing these pieces together in an impossible setting, he totally changes the context of the object. Through his obsessive preciseness he creates optical illusions. Cutting out shoes, boots, brooms, brushes, baskets, Gökcebag demonstrates his humorous approach, but his sincerity in searching the possibilities results in a certain fascination.

Gökcebag’s photography projects are also the products of a similar approach. He cuts fruits and vegetables in pieces and organises them extremely carefully to create a texture. Then, rather than directly exhibiting these objects, he photographs them. As a result of his precision, for the extremely impossible-looking scene, he has to add the information “not digitally manipulated” on the description tag of the photographs.

Semi Realities is another series of installations that create illusion through transforming the three-dimensional setting to a two dimensional surface. Half of the object remains untouched but the other half is cut into little pieces and stuck on the wall completing the shape of the object. . He also produced wall installations out of wire and pencil drawing in this series, which he used for Seriously Ironic. This time the shadow of the work becomes the subject for creating illusion by bringing three- dimensional objects and two-dimensional representations together. In Semi-Realities the illusion created by the transformation of graphical approach into three- dimensional space is continued. Using wire as a three-dimensional object with its reproduced shadow out of pencil, he mixes the line-like shape of the wire and pencil traces before the eyes of the viewer.

GözdeIlkin’s main concerns are human in society, alienation, sexual and social identities, power relationships and status issues. Although she uses various techniques and materials, the main element in her works is stitching. Through stitching she creates detailed figures, amorphous images, abstract compositions, scripts and many other forms.

In many of her works, Ilkin combines figures with either furniture-like objects or other undefined appearances. She hides her themes within the small scale framework and simple pretty figures. She uses stitching as a method of drawing in a detailed mode. By doing this, she actually transfers any possible pain she is going through with her themes.

In Seriously Ironic, a series of these stitching-drawing pictures are shown. The selection of the pictures is most representative of her work on feminine identity issues. The amorphous shapes of the heads attached to the female bodies are dealing with the identity crisis of women in society existing through beautiful bodies.

The installation piece Get Married, Be Happy is an ironic approach to the traditional system of marriage, whereby, in time, the woman gets emptied out and the man gets filled in. It’s a very simple setting that analyse the ways in which female identity is lost in the patriarchal system.

Devrim Kadirbeyoglu works using a variety of techniques and materials. Her subjects are on themes around violence, death and human brutalities. In explanation of her pessimistic approach, she declares: “If the results are disturbing, it’s because life itself is, in general, disturbing”. As oppose to this, her work is quite joyful and humorous. Growing up in an era after the military coup in 1980 and being brought up by a family that gave her a name that means “revolution” she maintains her seriousness in selecting her concepts; however, being a child of 80’s perhaps keeps the wild side of her personality awake during her production process.

Kadirbeyoglu is particularly interested in issues of migration and Turkish citizens facing many sorts of problems from having to obtain visas for travelling to living abroad. Her personal history – her experiences in the US where she lived for eight years to undertake a graduate degree – must have been decisive in her choice of this subject. Her videos of interviews with people applying for visas, and the installation she made by reproducing her own US visa, are from the same body of work.

For Seriously Ironic the artist is represented with an installation. In Case of Loss, Please Return To consists of three sculptures that the artist produced during her residency at Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center in Istanbul. The point of departure for this installation comes from her amazement by the number of gloves that she kept seeing on the streets of New York City. These gloves collected by the artist on cold days from the streets, subway stations and stores in New York were in most cases hardly used, expensive, and usually elegant.

The first piece of the series, which is the “mother figure” of this family-like setting, is a jacket sewn from these found gloves. The jacket is presented on a second hand sewing mannequin and comes with simple instructions on how to make your own. Kadirbeyoglu wanted to find the cheapest or even a free way to produce a very protective and elegant jacket for the homeless. On the other hand, the artist explains “…discarded objects and fleeting experiences have been picked up, collected, and remembered to be reassembled and reused”. The “father figure” of the installation is activated by a heat thermometer, which stimulates the sculpture when the temperature drops below the designated degree. When it is cold enough, the sculpture starts rubbing his hands to keep warm by the help of a motor. The “child” also rubs his hands, however only with help of a viewer. It’s manually cranked through its found hand drill structure. Every element used for this project is recycled.

Ferhat Özgür is a photographer and video artist. At first glance, the black humorous “mises en scenes” in suburban areas attract one’s attention. These scenarios are mostly absurd, irrelevant, colourless and probably not very attractive. However, his work requires a deeper look for the necessary communication to occur.

The artist lives and works in Ankara, the capital of Turkey, and this has been a key influence on his work. Ankara is the symbol of modernization and republicanism in Turkey. Ankara was just a small town in the middle of Anatolia before being designated as the capital of Turkey in 1923, after which point it became the centre of Republican architecture and sculpture. However, like many cities in Turkey, the outskirts of Ankara expanded more rapidly than the city centre and this created two contrasting structures: the modernised centre and the suburban poverty. Together they symbolise the failure of the modernization process. Ferhat Özgür shows a great interest in this issue of the conditions and politics of the outskirts. He is also one of the few contemporary artists in Turkey who despite not living in Istanbul is still able to show his work nationally and internationally.

The video piece exhibited in Seriously Ironic, entitled Its Time to Dance Now, deals with the suburban issue together with the most popular issue of Turkey’s recent history: the veil. The relation of the veil with socio-cultural, economical, ethical, religious and political structures is a significant theme in the everyday speeches of society from various aspects. Özgür brings up this humorous approach by placing a model dancing to hip hop music in front of a suburban setting. With simplicity, it summarizes the ridiculous state of this argument.

Our Neighbourhood and Shanty Angel are photographs from 2006. In these photographs, which suggest a similar setting to the video piece, Özgür creates confrontations between people and the area in which they live.

Let’s Everybody Come out Today is a diptych. The action taken by the artist in the preparation process of this photograph constitutes a middle way between political demonstration and public art. It is taken in the neighbourhood where the artist grew up and lived until his teenage years. The street is located between a semi-open prison and Great Ankara Hospital. He goes to this neighbourhood, knocks on everbody’s door and invites them out. He makes them stand in a line that might not be possible to be repeated in the future and finally creates the photograph.

Serkan Özkaya’s work varies widely in terms of genre and form. For that reason, it is very difficult to identify his work according to these values. The common ground for his work would be “irony”. Each work he produces creates a certain sensation through its setting.

Reproduction has been one of his major themes: questioning the meaning of the authenticity of an artwork. Özkaya has analysed this concept with different approaches in his work. One of his very well known works, tracing the recent history of contemporary art, was the project where he reproduced by hand the entire front page of a widely-circulated Turkish newspaper, under the title Today Could Be a Day of Historical Importance in 2003. This was made on the opening day of the Istanbul Biennale in 2003. It was a public art to be bought with a few pennies. Afterwards, he reproduced this project worldwide through various prestigious newspapers, including The New York Times.

Another of his sensational works is the 9 meter-long three-dimensional fax reproduction of David for the Istanbul Biennale in 2005. This gigantic sculpture tragically broke down right before it was placed on its plinth, before the biennale opening. It never got the chance to be shown.

The installation piece taking place in Seriously Ironic, A Sudden Gust of Wind was produced in 2008 for the first time. The only materials used for this very impressive installation are the A4 facsimile papers and invisible fishing wire. Representing the very moment of the effect of wind in an empty room through very simple and inexpensive material, the artist creates certain irony about the relationship between the price of artwork and the expense of producing it.

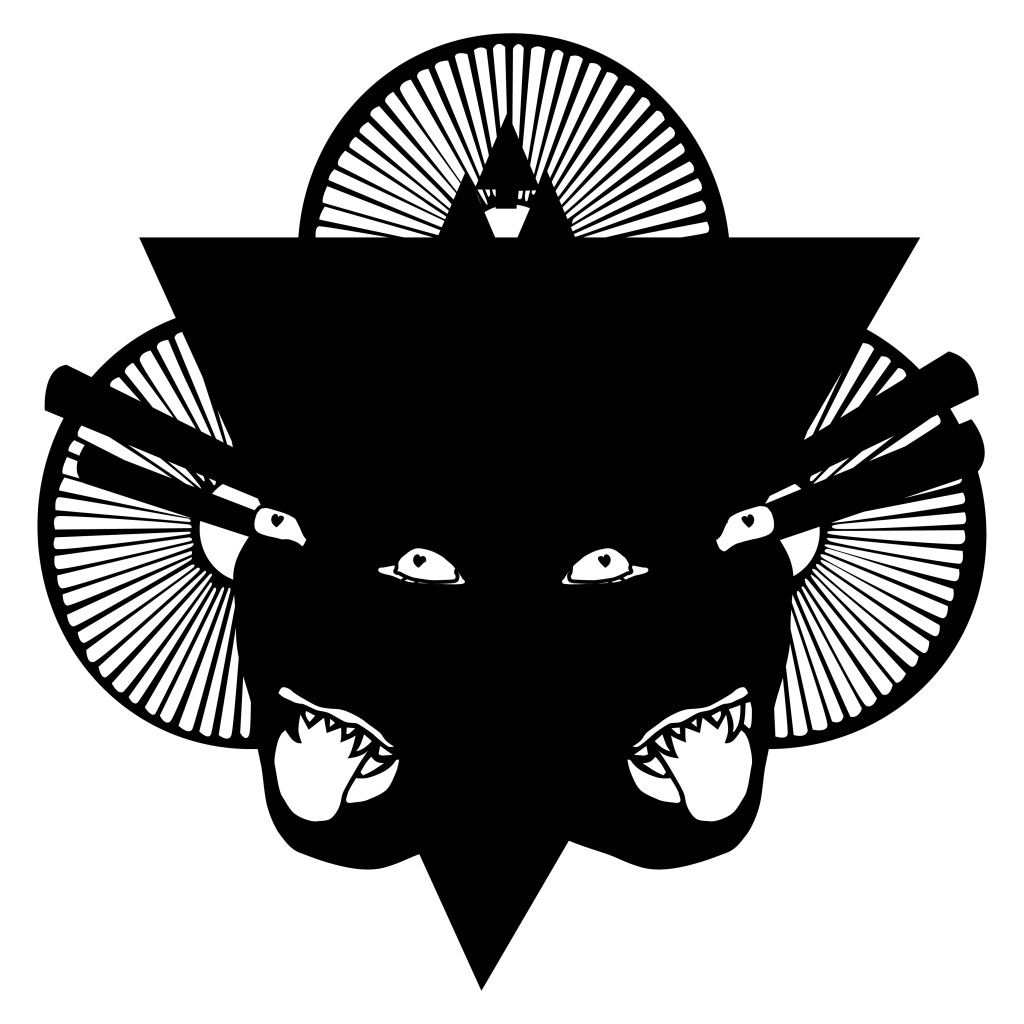

Hayal Pozanti produces her work in various forms. Through a contemporary graphical perspective, she creates fictive imagery, which simultaneously reflects on both the vicious and attractive aspects of human beings. Her paintings are dark and scary on one hand, aesthetically pleasing and fascinating on the other. Through analysing the limits of human brutality in her work, she twists the context of generally accepted norms of beauty.

Pozanti demonstrates a great interest in the darker and threatening sides of humanity and chooses subjects such as violence, serial murder, and war atrocities. However, although many clues are given in her work around these themes, she always leaves an unknown part for the viewer by keeping most of the story secret for herself.

Not dissimilar to her various series of paintings, in Kingdom Pozanti creates her own fable with fictive characters. In doing that, she invites the viewer into a very serious, and sometimes disturbing, game. The sweet, joyful characters in a deeper look represent her criticism of the existing values of the patriarchal systems through a very cruel and dark mental position. Pozanti neither clearly elucidates for the viewer, who has which role in this fictive society, nor gives clues for it, but simply opens up a space for the viewer to encounter the darker side of her mind.

Hale Tenger’s main interest is the history of the humanity. She explains very clearly her point of view in the interview with art historian Ahu Antmen in her recently published book entitled Stranger Within:

“The way humanity keeps boasting about its own achievements has always seemed pathetic to me. Not because I’m against ‘progress’, but because I find this constant attempt to claim a share from it absurd and humanity’s self-conceit seems pretty bizarre to me. In addition to all that has been achieved in the name of ‘progress’, there is also what remains unachieved. Neither the failures nor the great costs of these ‘accomplishments’ to humanity are taken into account and I find this unbearable. It is not clear where humankind is heading and its current state is not looking good at all.”

Tenger produces her work in a wide variety of media, but one clearly sees that her main intention is creating an atmosphere rather than simply showing a work of art. Her work invites the viewer into her political, artistic and personal territory.

The video Beirut, shown in Seriously Ironic, was shot shortly after the assassination of Rafiq Hariri in Beirut in 2005 and it was completed with the inclusion of the bombing sounds of the Israeli attack in 2007. The video consists of the façade of the once-glamorous hotel St. George waiting for renovation, with white curtain-like fabrics as if floating, smoothly with the gentle breeze coming from the sea in the daytime, and at night, being battered by a much dramatic inland breeze. The fully white fabrics in this abandoned building may be easily associated with the peace flag in the viewer’s mind. While the video was shot, the crater formed by the Hariri bombing was still there, right next to the St. George Hotel. The white fabrics were supposedly hung on each gateway of building’s balconies as a protest against the delay of renovation permission as the artist heard at that time. This protest created an astonishing, and perhaps unexpected, visual effect with the help of the wind and led the artist to secretly film it from her hotel room since taking photographs or making video recordings was not permitted in this area which was under U.N. military protection.

The tension between the smoothness of the daytime and the horror of the night was emphasised by the music composed by Serdar Ateser and successive audio of bombings.

Mürüvvet Türkyilmaz produces very delicate work that is both conceptually and manually embroidered. From her very early period till now, her work demonstrates an admirable consistency.

The chosen images, objects and techniques run around in a circle in her work and come back in a fresh context. In the same way, her artworks proudly exhibit the evident long-term thinking and production process.

The work of Türkyilmaz is very much concerned with geography and cartography in broad spectrum. She deals with borders and boundaries from various aspects, and describes her work as “a journey on the physical as well as the political map”. Through this journey, Türkyilmaz applies various techniques and methods. Drawing by means of scripts is one of her much personalised techniques where she deals with her selected concepts simultaneously reflecting her personal presence.

Geography of Fear is an example where the artist uses script drawings to create a map dealing with the fear of terrorism, natural disasters, impact of technology, paranoia, etc. Fear of Thought, on the other hand, is an installation that rather suggests a brain map that consists of night lamps with portraits of people who are accused, killed or arrested for their thoughts.

Overjoyed Ones consists of six drawings of towers, these are: Babil Tower, Petrol Tower, Transmission Tower, Russian Tower, Minaret, Radio Tower. While indicating the horizon at the bottom of the drawings, Türkyilmaz highlights the ordinary and legendary ascending images of our lives. For this series of drawings, Türkyilmaz used the graphite technique as she also did in most of her earlier works. With this technique, she twists the concept of drawing, by simply leaving the borders blank but filling the inside and outside of the images. Being interested in subjects such as geography, borders, maps, mapping, fragmentation, loneliness and their relation to time and space, Türkyilmaz questions the dilemma caused by the vertical structural elements forcing the boundaries of our horizon. By studying on these vertical images, on one hand Türkyilmaz analyses the role of these architectural structures in our physical and political life, and on the other, looks for her own place among their unavoidable presence.

Hande Varsat departs from her personal history, family traditions and socio-cultural experience in her work. As a central Anatolian girl raised in a traditional setting yet educated in modern American schools, she always experienced the dualities and contradictions in many aspects of life. Awakening her femininity was perhaps the strongest confrontation of them all. She faced and shared the internal conflicts of the women surrounding her, who are under pressure about honour, virginity, virtue, marriage and many other issues that generate the local feminine identity.

It is possible to feel expressions of displeasure and revulsion at the same time as acceptance and forgiveness all in the same work. She declares: “The expression mechanism in my works is based on staying away from scatological politics of feminism and keeping a poetic rhythm that forms its beat by hygienic symbols that refer to Turkish traditions and ethics.”

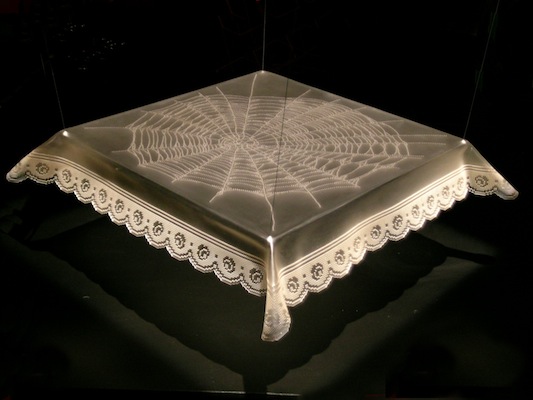

Three of the works taking place in Seriously Ironic represent the cultural fact of ‘trousseau’, which is a heavy duty for the young women to prepare prior to marriage. It is a heavy duty in various aspects. First of all, the artist makes the point about a culture where flirting, loving and touching are intolerable before marriage, or even after. The two sexes are separated in society and often brought together in arranged marriage, where the young women are mostly selected by the men’s families, requested from their parents and taken against their own will.

Interval Table is a hand-shaped Plexiglas punctuated with twenty seven thousand holes. The tablecloth is one of the most important elements of the bride’s trousseau, which was originally produced by embroidery. More than its use – especially in modern times, where the fashion has changed and factory-produced tablecloths are more in use – it is more of a symbol of the preparation for marriage. The depiction of the spider web on top of Interval Table seems to represent the women trapped by traditions.

The Threshold Inside goes a step further and questions the internal conflict of the young woman getting married. Through these dual images, Varsat connects the manual and mental labour of the preparation for marriage with protecting chastity and, so to say, the honour of family. The hole of the perforated objects represents the hymen and all the information hidden behind it.

Steal the Handkerchief refers to a game where girls compete to catch the handkerchief so their wish for marriage will come true. Varsat twists the context of the game here, showing the girls that the dream they have is actually going to be a hook to trap them within the traditions.

texts by Isin Önol

photographs by the artists

MORE IMAGES FROM THE EXHIBITION:

- Hayal Pozanti, +//LUX//+, painting on wall, 2009